🗓️

2025

Code or no code that is the question

Why learning to reason with machines will matter more than learning to program.

For over fifteen years, the same refrain has been repeated: children must learn how to code.

Associations, governments, schools, and startups all insist that "coding is the new writing," "the language of the future," "the essential skill to avoid being left behind." Python has been presented as the new English, Scratch as the new intellectual coloring book, and the developer as the archetype of the job of the future.

Yet one fact remains: very few humans know how to code.

Despite fifteen years of talk, the proportion of the population actually capable of writing and maintaining serious code remains minuscule. And, at the very moment this discourse gained traction, another revolution arrived: Language Modeling Languages (LLMs) capable of writing code for us.

In this context, a question becomes urgent, almost brutal:

Should we really teach our children to code? Is it a skill in which it is intelligent to invest, now?

Code as machine language: still crucial, but increasingly mediated by LLMs

Let's start with an obvious point that I don't seek to dispute: code as a machine language still has a bright future ahead of it.

Everything that runs today—operating systems, servers, applications, video games, industrial robots, networks—relies on code: C, C++, Java, Python, Rust, Go, and many others. None of this will magically start working without code. Even the most sophisticated AIs run on extremely complex software stacks, themselves hand-coded.

But something decisive happens: models like GPT-4, Claude, or other LLMs become capable of:

generate code on demand,

to correct it,

to test it,

to translate it from one language to another,

and even propose complete architectural designs.

Code is no longer something that only an initiated human can produce. It is becoming a material that can be invoked, manipulated, and transformed through natural language. We are already beginning to move away from "programming" directly and toward interacting with an assistant that programs for us.

Code remains fundamental. But its place is beginning to change: from direct human practice, it is shifting towards an infrastructure layer managed by automated systems.

"Yes, but we will always need people to code the LLMs."

Faced with this, an initial reaction emerges: okay, LLMs can help with coding, but humans will still be needed to code the LLMs themselves. People will always be needed at the heart of the machine.

That's true. But that doesn't change everything.

Yes, there will still be people to code the models, frameworks , low-level libraries, compilers, and system kernels.

Simply:

These are extremely specialized layers.

They concern a very small number of experts,

and the natural tendency of computing is to concentrate more and more intelligence in these deeper layers to simplify the upper layers.

That's exactly what happened with assembly language. There was a time when a large proportion of programmers worked directly in assembly. Today, very few do. Assembly hasn't disappeared: it's everywhere, but buried in compilers, libraries, and firmware . We need it, but almost no one uses it manually anymore.

The same trend is emerging for "classic" code in relation to LLMs: it doesn't disappear, but it becomes less common as a direct human practice. You don't need an entire continent of developers to maintain the deepest layer.

"Yes, but we'll always need a little bit."

Second fallback: very well, less will be needed, but it will still be necessary. Code will remain critical; we will always need developers, even if most of it is automated.

Again, the answer is: yes… but.

Yes, developers will still exist, just as there are electronics engineers, theoretical physicists, and embedded systems specialists. But, for the majority of the population, this layer will become as distant and invisible as the core of an operating system is today.

We all use an operating system every day – Windows, macOS , Linux, Android, iOS – but almost none of us have the slightest idea what goes on in the kernel. We don't write device drivers, we don't manage memory, we don't schedule threads.

It's not that it no longer exists. It's that it has become:

invisible,

encapsulated,

manipulated by a minority of experts,

and completely absent from the user's daily experience.

Code is following the same trajectory: becoming more and more indispensable, less and less visible.

"Yes, but we can always change the paradigm, invent something else."

Third reaction: we can always invent something else, change paradigms, conduct research, explore new forms of programming. Innovation will not stop.

That's true, and even desirable. But here too, there's no guarantee that this area of innovation will remain human-centered.

In principle, nothing prevents AI from:

explore new programming languages,

to propose innovative architectural designs,

to find more efficient compilation methods,

generate their own computational paradigms better suited to their own capabilities.

In other words, even "code research" is no longer guaranteed to be a domain reserved for humans. And in reality, it already is: AI systems are helping to design algorithms, optimize circuits, and prove theorems.

What remains specifically human then shifts: no longer so much in the making of the machine, but in the definition of what we want to do with it. Less in the syntax, more in the meaning.

"Yes, but basic research will remain human-centered."

Fourth refuge: fundamental research, abstract thought, and radical creativity would remain the preserve of humans. Even if AIs can code, they would not reach that level.

That's a hypothesis. It's no longer a certainty.

We are seeing the emergence of AI capable of:

to propose conjectures in mathematics,

to help find evidence,

generate ideas for scientific experiments,

to explore spaces of solutions that humans would not have had time to explore.

This doesn't mean that humans are out of the game. It means that the boundary between "what the machine can do" and "what remains human" is constantly shifting. And that this boundary probably isn't simply "knowing how to write code."

This leads us to a crucial question: what can code do that language cannot?

What can code do that language cannot?

Let's put this question clearly:

What can code do that language cannot?

The answer, if we take the problem seriously, is baffling: nothing essentially different .

Code isn't some magical substance that can do something natural language can't describe. Code is already language. It's simply a language.

strictly formalized,

deliberately impoverished,

structured to eliminate ambiguity,

optimized to be interpreted by a machine.

What made code so powerful compared to natural language was:

its precision,

its lack of ambiguity (in theory),

its ability to be executed automatically.

But LLMs change the equation.

They allow, for the first time on a large scale, taking natural language and making it operational. They make possible, at least potentially, a nuanced and contextual interpretation of our sentences, our intentions, our scenarios.

The bottleneck is no longer the syntax of the programming language, but the clarity of human thought. The real question becomes:

Are we capable of thinking clearly enough to describe what we want?

Are we capable of formulating detailed constraints, strategies, scenarios, and behaviors in natural language?

If the answer is yes, then natural language, supported by AI models, can do at least as much as code — and often more, because it is more expressive, richer, closer to our way of thinking.

From "knowing how to code" to "knowing how to think with machines"

This is where the shift occurs. Until now, a very specific skill was valued: knowing how to code.

Knowing how to code meant:

mastering a language (or several),

understanding data structures, algorithms,

to organize a program,

debug , optimize, maintain.

This skill remains useful, but it is no longer the core issue. As LLMs take over code production, the rare skill becomes something else:

knowing how to ask the right questions,

knowing how to formulate a problem,

knowing how to explain constraints,

knowing how to orchestrate systems,

to judge whether what the machine proposes makes sense.

Humans who, yesterday, had no technical skills will soon be able to:

designing autonomous agents,

orchestrate entire workflows,

to create complete software packages,

simply by describing what they want, in natural language, in a sufficiently precise manner.

The key will no longer be knowing Python syntax, but understanding:

to describe a situation,

to anticipate special cases

anticipating behaviors,

to structure an operational line of reasoning.

This is exactly where the concept of brain comes in .

The brain : the programming unit of tomorrow

A brain , as conceived in systems like Hyko, is not just a program. It is an architecture of intentions, rules, and behaviors.

A brain is:

a way of thinking about a task,

a way of ordering actions,

a way to react to unforeseen events,

a way to communicate with other brains or other humans.

And this brain can be largely defined in natural language: through descriptions, scenarios, constraints, and examples. From there, the machine can generate the necessary code, infrastructure, API calls, and software architecture.

It is no longer the code that is at the center, but articulated thought . The brain is the interface between human intelligence (formulation, intention, purpose) and machine intelligence (execution, optimization, adaptation).

In that world, traditional programming languages still exist. But they become the underpinnings, not the place where visible intelligence takes place.

The code becomes part of the OS: invisible, omnipresent

This is the crucial point: the code as we know it will not disappear. It will become invisible.

It will become part of the operating system, in the broadest sense:

kernels ,

AI frameworks ,

agent platforms ,

cloud infrastructures ,

bookstores .

We will use code constantly, but without seeing it. Just as we use operating systems without ever interacting with their core, we will use extremely sophisticated layers of code without writing or reading them.

Languages like Python, C, and C++ will continue to exist, but only for a minority of experts who will maintain these deeper layers. For the majority, the main interface will be:

language ,

brain design interfaces ,

workflow description tools ,

systems for dialogue with agents.

The act of "programming" will shift from visible code to conceptual configuration: how I want my system to behave, what it must respect, what it is allowed to do or not.

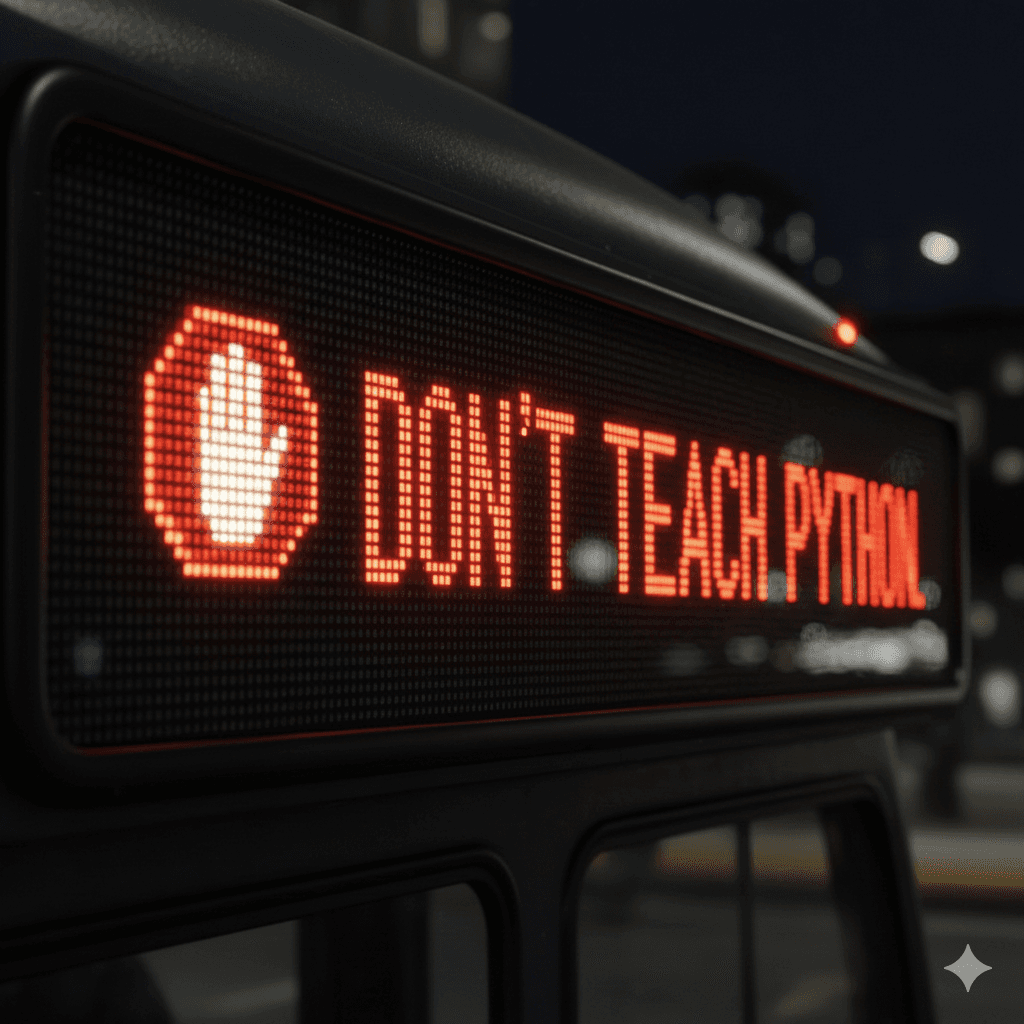

So, should we teach our children to code?

Let's return to the original question.

Should you teach your children to code?

Is it a skill worth investing in?

The answer, in my view, is twofold.

No, if "learning to code" means:

locking them into learning a specific syntax, a particular language, as if the future of their employability depended on their ability to write for loops and classes by hand for forty years.

Yes, if "learning to code" actually means:

them to think in a structured way,

to understand what an algorithm is,

to grasp the logic of a system,

to be able to formulate problems clearly,

learning to communicate with intelligent machines.

Code, as a low-level human practice, will shrink, become more specialized, and invisible to the majority. But the ability to think like a systems architect will become central.

The future does not belong to coders in the narrow sense, those who simply pile up lines of syntax.

The future belongs to humans who:

think well,

think astutely.

think effectively

know how to combine their intelligence with that of machines.

These are the ones who will know:

to describe what they want with great conceptual precision,

evaluate what the machine offers,

adjust , correct, orient,

design brains rather than scripts.

In this sense, the question to ask our children is perhaps no longer: "Should they learn Python?", but:

Do they know how to formulate an idea clearly?

Do they know how to break down a problem?

Can they imagine a scenario, foresee exceptions, anticipate consequences?

Will they be able to communicate with machines in a way that they can understand?

The code will continue to exist, but behind the scenes.

What will come into the spotlight is our capacity to think – and to work with artificial intelligences capable of transforming our words into worlds.